Where Are Young Voters In Oregon’s Toss-Up Governor’s Race?

October 30, 2022

The state of Oregon is facing a notable political shift in the upcoming November elections. The culmination of many long-present social and economic issues have led to a disgruntled voting base. Roughly two-thirds of Oregonians don’t think the state is headed in the right direction.

The severity of housing, crime, inflation, climate, and abortion rights have led to increased dissaproval of Oregon’s elected leaders — particularly the govenor. As of October, Governor Kate Brown has a 50% disapproval rating according to Morning Consultant; putting Brown as the second least-popular state governor in the country, behind Matt Bevin of Kentucky. Under Oregon law Brown cannot serve for more than two terms, and the election to replace her has become the most contentious in decades.

Predictions and analyses have attempted to identify the broad preferences of Oregon voters in this race, yet commonly overlooked is the role young voters will play. A new year of eligible voters will be able to cast their first ballot this November, including a large portion of Ida B. Wells’ senior class.

Background for the Race

Entering the election season voters anticipated an open governor’s race, the first in 20 years to have no incumbent or clear nominees. This has created a highly eventful gubernatorial race, with candidates declaring their candidacy in as early as November 2020.

The Democratic primary election ended a largely two-way race between State Treasurer Tobias Read, and then-Speaker of the State House Tina Kotek, with Kotek succeeding over her more moderate rival by roughly 25 points. Regionally, Kotek carried western Oregon while Read found more rural appeal in Oregon’s eastern counties. Briefly, the race was predicted to be three-way with the entrance of New York Times journalist Nicholas Kristof before he was disqualified due to legal issues of residency.

Republicans faced an energized primary race between nearly 20 different candidates, including 2 previous nominees, 2 state representatives, 4 local officials, and numerous businesspeople. Ultimately then-State House Minority Leader Christine Drazan received party leadership support and narrowingly won the nomination with 23%.

Outside the major parties, former Democratic State Senator Betsy Johnson announced her candidacy as an unaffiliated candidate in October 2021, and has campaigned on a centrist message condemning extremism on both sides. Other candidates on the ballot include Leon Noble of the small-government Libertarian Party and Donice Noelle Smith of the conservative Constitution Party.

Evident in this race is Oregon’s lack of campaign finance regulations, which includes no limits on the amount of money a candidate receives. Despite Johnson initially leading with business and corporate-backing, millions of dollars have been invested in all three candidates from corporations, labor unions, and national party funds. Current numbers show Kotek’s campaign to have raised more than $21,400,000 dollars, Drazan with $18,700,000, and Johnson close behind with $15,000,000. The Democratic and Republican Governors Association have backed their respective candidates heavily as party leadership finds the race increasingly competitive.

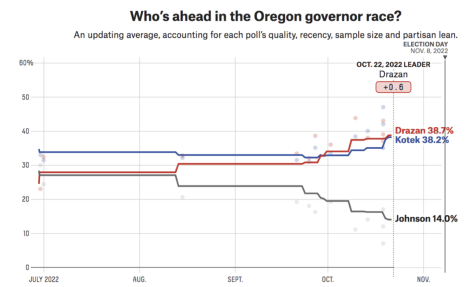

News outlets and data analysts have studied the makeup of the Oregon electorate thoroughly for this race. Party preferences have varied in polls, leaning to both parties in early 2022. A late September study by Clout Research found a 50-50 dead-split between favorability towards a Democrat and Republican candidate. Polling of the candidates themselves has mostly found Republican Drazan to lead within the margin of error, followed closely by Democrat Kotek, and Johnson behind by more than 10 points. News media predictions for the race have shifted from “Lean-D” to “Tossup”, finding no clear lead.

The outcomes of this race could dictate the condition of life in Oregon for as long as 8 years. Partisan issues such as gun violence, policing, and abortion could be dramatically affected depending on who is elected Looking to a voting demographic that encompassed 17% of those who participated in the last election, Oregonians aged 18-30 could be in a unique position in determining the winner.

“If you sort of think of your physics, they have that potential energy to dominate politics. But it’s just contingent on them deciding to participate,” said John Horvick, senior vice president at DHM Research, a popular polling group in the northwest area.” Horvick has served as president of the City Club of Portland, and can be frequently seen as a political data commentator on local cable news. Via phone interview, he shared his findings and perspective on young voters’ patterns and positions. Despite still representing a solid block of the electorate, younger voters don’t vote as frequently compared to other age groups.

“In the state of Oregon, when they post their post election statistics, they rank the age categories 18-34, 35-39, 40-64, 65+,” Horvick said. “If we look at turnout among 18-34 year olds, we know for sure that turnout is even less than the national average. Turnout among 18-34 in 2018, the last midterm election, the last gubernatorial election, was at 51%. Turnout among voters 65 and older was 86%.”

Yet there is nuance, especially when comparing these voters to the oldest generations, there is a peculiar relationship.

“There are more registered voters who are 18-34 than there are 65+, but there were more people who voted who were 65+,” Horvick said.

The Ida B. Wells Vote

There are a variety of factors for this low turnout, Ida B. Wells senior Alex Peltz is a politically engaged student who registered to vote, and has recently received his ballot in the mail. Peltz provided his personal guess for why his age group doesn’t turn in their ballot.

“Mostly I would say probably because people have a lot going on in their lives, especially end of high school,” said Peltz. “If they’re in college and it’s maybe just something they don’t think about or just don’t get to and they don’t think it matters that much.”

But he breaks down why voters his age need to go against this trend and actually participate.

“I think if you’re a citizen and if you care about what happens to you, then it’s kind of your job to participate in it,” said Peltz. “And especially this year when the margins are really tight, it can mean a lot. It’s not something you can just kind of phone in and not care about.”

Horvick identifies 4 different reasons why the youth isn’t politically engaged as much: routine, lifestyle, investment, and understanding. “There’s lots of reasons political scientists have looked at, and there’s probably some truth to all of them,” said Horvick.

“One of them is that you gain age, and you get in the practice of voting, you become more consistent at it. Part of it is just practice. Another is that younger people are less settled in their life.” He cites life changes like moving to college, finding a new job, and relationships as common disruptions.

“Another thing is as you get older, elections may be more consequential for you. You pay more in taxes, you know more about local or statewide issues because you have more time to learn about them.”

Horvick’s last reason for this was confusion. He says young voters may not be familiar with the election process and the issues. In addition, this can culminate into a sense that your vote doesn’t matter.

The lack of understanding factor may also be a matter of focus. Young voters may be in-step with the recent phenomenon of an increasingly nationalized political climate. The differences between local and national issues have become less present, and in turn candidates have become increasingly aligned with their national party rather than local identity. Washington D.C. is now as relevant in Oregon politics as Salem is.

“Part of that is the media landscape, that there’s less local news than there used to be,” said Horvick. “24-hour cable news is really good at creating that shiny object we all want to look at. State politics has become a lot more national.”

His work has found that voting patterns for all ages are less varied and more partisan.

“People used to split, say vote for Democrats in the congressional races and Republicans for president or vice-versa. That’s pretty much not true anymore.”

“Are young people gonna be involved in local elections?” Horvick doesn’t see the young vote being any more immune from the effects of this trend. “Maybe, but my guess is that unless these bigger structural things change, young voters will be like the older voters in which they will pay more attention to national issues, and vote for president with stronger feelings than say their state representative.”

Peltz explains his preferred news sources are usually nationwide, a reflection of what Horvick states is a common phenomenon.

“I’d definitely say that I’m more interested in the bigger national stuff mostly because of how I read the news; through things like Apple News and the New York Times and some of the bigger news outlets.” said Peltz.

He also expressed skepticism to vote in line with a single party. “I’m not just gonna mark them down because they have a D next to their name, but the chances that I would agree with a Republican is not very high,” he said.

Peltz laid out problems such as homelessness, reproductive rights, education, and LGBTQ+ rights as issues he will be voting on this November. As a Portlander who travels frequently to the city’s east side, he has found homelessness to be a particularly visual crisis. He sees Christine Drazan unfavorably with her non-committal position on abortion, as he thinks she will do little to defend it. He also later expressed fear of the anti-CRT movements potential effects on education, and notes LGBTQ+ and transgender causes to be a ‘dealbreaker’ issue for him. When he goes to vote, Peltz’s choice for this election is clear.

“It will be Tina Kotek, mostly because she just aligns best with the ideals that I have.” said Peltz.

Specifically with their political beliefs, 18-30 year olds this election season find much overlap on the issues with their older counterparts, with exceptions to the degree and some more progressive issues according to Horvick. Homelessness, crime, and housing affordability span all demographics as key issues.

“I’d hall out two [issues] as being different,” said Horvick. “Younger voters tend to prioritize and think differently about the environment, particularly around climate change they think is a more important issue and that more action needs to happen. The other is around crime and public safety policing, younger voters are much more skeptical of policing as a solution to public safety issues than older voters are. But these are differences in degree, younger voters will also tell us they want more policing.”

Horvick digressed further with the relevancy of climate change as a voting issue this election and its popularity compared to other problems mentioned. He explained climate change is still considered by most voters to be an important issue, yet does not rank as high as homelessness, crime, housing affordability, and government dysfunction have in public surveys.

Student voter registration was held by the school earlier this month in the cafeteria to give assistance to those eligible seniors. This provides a positive outlook for young voters who may actually involve themselves in this election. The state has been rated as one of the easiest places to vote in in the nation, in part due to automatic voter registration when you attain your license at the DMV, or the main-in ballot system implemented in 1998.

Many Oregon voters have been following this race closely, likely including those whose future will be most affected by the next governor. A generation that has lived through record levels of partisanship, lack of confidence in leaders and media, and all levels of governmental dysfunction is now becoming eligible to vote.

Whether the younger demographic will overcome life barriers and utilize their potential energy to invest locally is yet to be seen. The victor of this governor’s race may also be the candidate who made the best outreach to the young voters of the state. Registered seniors of this school have a say in these midterm elections, and a possibly decisive vote in a historically contentious state race.

“On the grand scheme of things one vote from an individual’s perspective doesn’t really matter.” Peltz says. “But once that mindset applies itself to thousands of people then that starts to matter.”