Southwest Portland’s Historic Signs

February 10, 2023

Signs have graced Southwest Portland since the area’s earliest days, when the current site of Ida B. Wells was the Fulton Park Dairy, interurbans crisscrossed the valley, and the houses that now make up the Wells district were not even dreamed up yet. Almost all of these early signs, such as the ones that once hung outside post offices and train depots, are now long gone.

The signs that survive today were erected primarily in the 1940s and 50s, when Southwest Portland was experiencing unprecedented growth. During this postwar boom period, Southwest Portland, especially Barbur Boulevard, was home to a large concentration of neon signs.

As motels gave way to office plazas and apartment buildings, these once-ubiquitous signs were slowly turned off or dismantled, resulting in the loss of a crucial part of the area’s history. But despite this shift away from expensive, large-scale neon signs, some have survived and their neon keeps glowing to this day.

Constructed in the early 1940s, the Capitol Hill Motel sign is undoubtedly the crown jewel of Southwest Portland’s neon signs. Sandwiched between a locksmith, a poker club, and I-5, the Capitol Hill Motel is the best surviving example of what was once a typical sight on Barbur Boulevard. In its heyday, dozens of motels lined the highway between Potland and Tigard, each beckoning to travelers with a unique neon sign.

Over the years, this number dwindled as the City of Portland annexed the area and fields gave way to developments. At the same time, I-5, which runs parallel to Barbur in this area, sucked cars off of the highway, leading to a decrease in the demand for lodging. Today, just two motels built during this golden age of Barbur are still in operation: The Ranch Inn, and the Capitol Hill Motel.

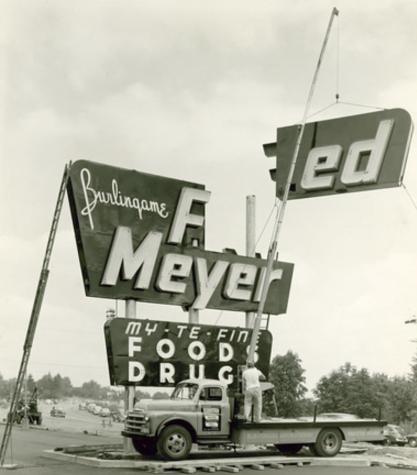

The Burlingame Fred Meyer has always been something of an unofficial community center for Southwest Portland. Initially constructed in 1950 and expanded in 2011, this is the oldest Fred Meyer store, tracing its beginnings back to long before the chain was bought by Kroger. At the time of its construction, development on Barbur was still in its nascent stages, and the bond measure to construct then-Wilson High School had not yet been approved.

In the decade that followed, the Wilson Park neighborhood was constructed, gas stations and diners popped up all along Barbur, and Southwest Portland truly began to establish an identity of its own. During this period, the iconic sign that stands outside the store was surrounded by signs for Eve’s Restaurant, 76, and Burger King, home to the 19 cent burger, and not related to the national chain. Now, the Fred Meyer neon sign stands alone, welcoming shoppers to a store that is still the heart of Southwest Portland.

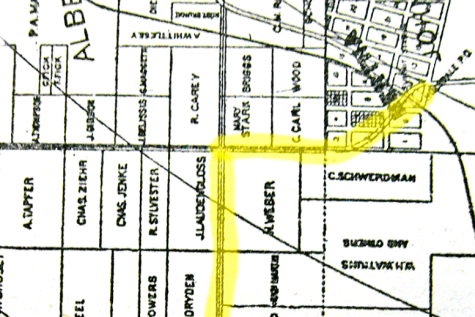

City records indicate that the Hoot Owl Market, located at the corner of Capitol Highway and Vermont Street, was built in 1930, around the same time as the neighboring Cider Mill Restaurant, which claims it has been in operation for nearly a century. Tax records and aerial maps, which only date back to the 1950s for the area, seem to back up that claim, but otherwise, very little is known about the Hoot Owl Market.

Today, the defining feature of the store is its neon sign, featuring green and red lettering and its inquisitive namesake owl. But the property where the market sits was once home to Rosa Webber, an early settler, who was the last holdout preventing the construction of Capitol Highway. Eventually, she caved and took $100 for 17,424 square feet of her land, allowing the project to move forward.

At the time, Capitol Highway was a highly publicized infrastructure project and a part of the Pacific Highway, which was the first road to traverse the Western US between the Canadian and Mexican borders. As its name suggests, this road, completed in 1916, wound through the Willamette Valley on its way from Portland to the state capitol in Salem, and eventually on to California. Since then, most of the road has been abandoned or realigned, but Southwest Portland is home to the last piece of this once-integral highway.

Though Capitol Highway, Barbur Boulevard, and the rest of Southwest Portland have changed dramatically in the last hundred years, these vestiges of the neon era stand tall. They serve as reminders of our past, when vast dairies grazed cows on rolling hills, motels with glittery signs lined the highways, and the gully that I-5 now sits in was home to nothing but woods and water. The roads and neighborhoods that we know today have countless stories to tell, and through their permanence and their prominence, signs tell those stories.