September 15 is an important date for many people of Mexican descent. Every year, there are numerous parades, ceremonies, and celebrations all throughout Mexico, and even in the United States. The city of Portland is also holding a ceremony for this monumental holiday.

But why is that the case? This is the day that El Grito de Independencia (The Cry for Independence), also known as El Grito de Dolores (The cry of Dolores), occurred. But what exactly transpired on September 15?

As you may remember in history class, El Grito de Dolores occurred on the night of September 15, 1810, in what is now known as Dolores Hidalgo, Mexico. A Catholic priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla was fed up with the oppressive government system that the Spanish implemented. So on that night, and onto the following day, Hidalgo held a speech for the people of Dolores. Many people from different backgrounds were moved by his speech and would follow Hidalgo and his idea for a revolt against the Spanish. This small army would eventually fail due to them being ill-equipped and not well-trained, most of them were just ranchers and farmers. The fight wouldn’t end with Hidalgo, however. In fact, the fight would last for 11 more years, switching between leaders every so often after a failed attack. During this war for independence, many heroes were born, and they are commemorated every year during El Grito.

El Grito Portland, an organization, makes a commitment to honor El Grito de Dolores every year. This year was the 213-year anniversary of El Grito, and the celebration is no different. The activities were rich with authenticity and flavor.

There were bailes folkóricos (folkloric dancing) from various Mexican states, such as Michoacán and Chiapas.

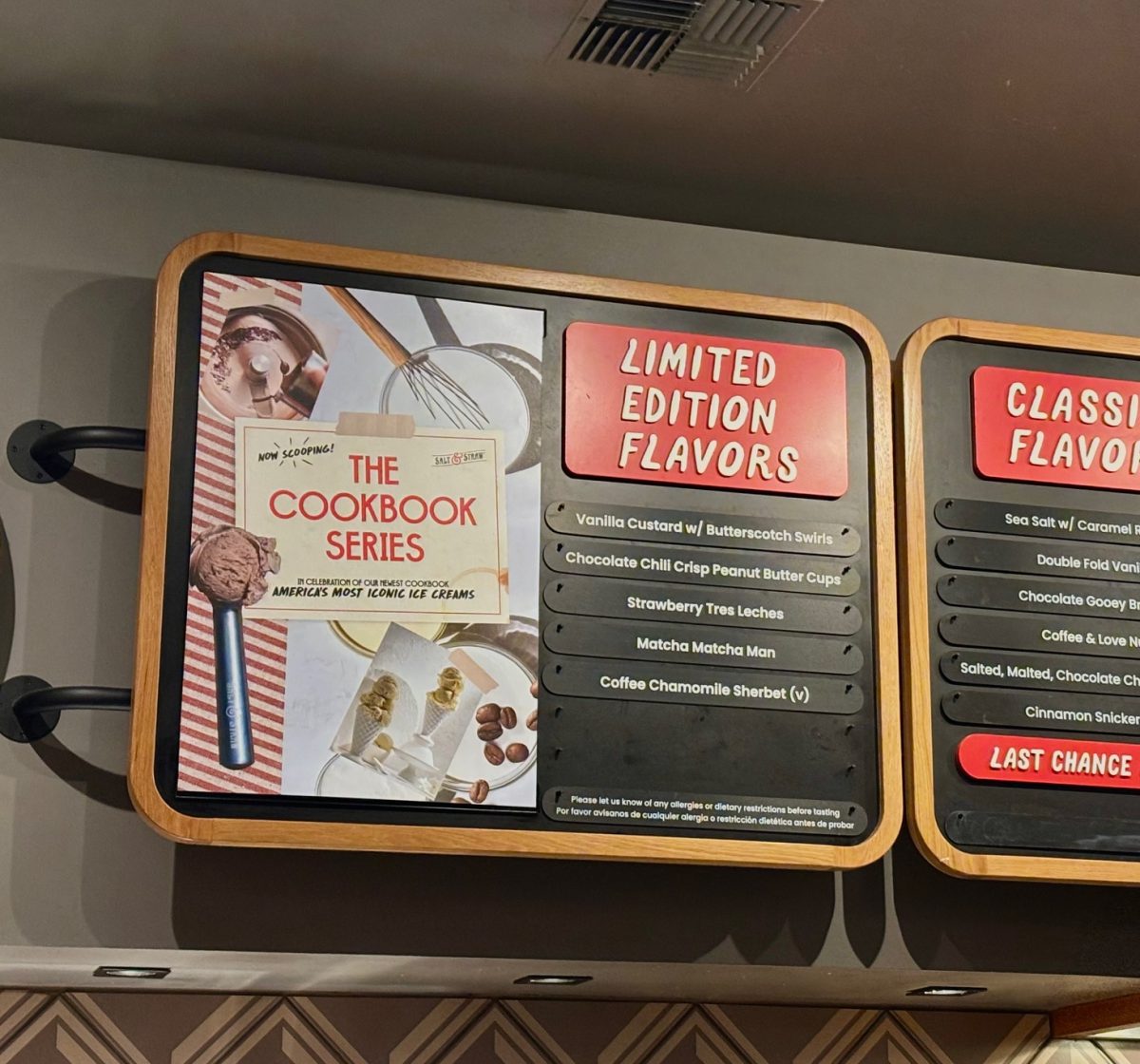

The food at the event was very authentic, with the most popular dish being the quesabirria. It’s a quesadilla with birria, which is a meat stew, usually steak, marinated with an adobo made from vinegar, herbs, chiles, garlic, and spices.

Woodburn High School would also perform at the event for they have their own mariachi band. They would perform classic songs from legendary and influential artists, such as Vicente Fernandez and José Alfredo Jiménez.

As the sun began to set, the actual Grito ceremony commenced. Firstly, the national anthem for the United States played, and the color guard marched. After the American color guard ended their march, the Escolta de la Bandera Mexicana (the Mexican color guard) started to march. When the Escoltas started to march, the historic Banda de Guerra played alongside them. The Banda de Guerra is a song that is played to pay respect to the Mexican flag. The song and flag were both made in 1821 and whenever the flag is being moved, the song must be played to respect the flag and the Escoltas. As the song plays, the audience pledges allegiance to the flag. The way to pledge is done by putting down the thumb and holding the hand in front of the heart. The flag bearer, followed by five Escoltas, marches through the pathway and would make their way to the stage where Carlos Quesnel, the head Mexican consul of Oregon, is waiting.

Yells and cheers could be heard throughout the crowd as the Escoltas Mexicanas ended their march. The flag bearer made her way up the stage to hand the flag off to Quesnel. “Mexicanos, firmes ya,” the announcer would yell to the crowd to signify to stand at ease. The crowd stood in silence, witnessing the beginning of the Grito de Independencia.

“Mexicanos, viva los héroes que nos dieron patria y libertad,” (Mexicans long live the heroes who gave us homeland and freedom) Quesnel yelled to the crowd. The crowd responded with, “viva” (long live). Quesnel would then list off the names of various heroes who contributed to the fight for independence. With this specific speech, whoever is giving el grito would start every line with “viva,” and the audience always responds by saying “viva.” He concluded the speech by saying, “Viva la Independencia! Viva Mexico.” Repeating “viva Mexico” three times, then he waved the flag around with the crowd cheering on. After, Mexico’s national anthem started to play.

The consul’s grito is extremely short, and is exactly what the presidents of Mexico would say during their own grito, except for the current Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). AMLO is known for his commitment for change and equality, and is the first president ever to add to the grito. He adds “muera” (die) to the grito, and lists off problems in modern society such as corruption, racism, classism, and more. The audience of course responds with “muera” every time AMLO says it. But this year AMLO would add to it again. He said, “Que vivan nuestros hermanos migrantes” (May our migrant brothers live).

The struggle for Mexico’s independence was a long, difficult battle. So it only makes sense for this to be the biggest celebrations in Mexico.