I vividly remember Jan. 6, 2021. At 9:00 a.m. my alarm went off. Three feet and 15 minutes later, I logged on to my 8th grade English class. It was followed by my US studies class, which was taught by the same teacher and had the same students. We’d finished learning about the “checks and balances” our governmental system was founded on, and from there we moved on to the bill of rights and the amendments.

That day in January we didn’t do much in English, all too distracted by the chat filled with links to live broadcasts and breaking news headlines. Behind our teacher’s head, half a TV screen, muted and with captions turned on, flipped between the different stations.

English quickly transformed into our government class, and our actual government class ended early with directions to go watch the news instead. I spent the rest of the afternoon sitting on the living room couch with my dad, listening to reporters debate back and forth, and watching people covered in face paint hoisting flags as they stormed the Capitol.

This class was my first introduction to the way our government works — it was online and I was in 8th grade. I will be voting in the next presidential election and I haven’t had a government class since.

In 2022, Oregon had one of the highest youth voter turnout rates; 36% according to Tufts University. To graduate in Oregon, students need to have completed 24 credits — including 3 social studies ones. According to Senate Bill 513, adopted by Oregon in 2021, and starting with the class of 2026, those three credits will have to include a half credit of civics.

The current requirement for the classes of 2014-2025 is three social studies courses that cover history, civics, geography and economics including personal finance. The new requirements are similar to the previous ones, just more specific — Half a credit of US civics with the addition of two and half credits earned in US history, world history, geography, economics and financial literacy. For many students, especially those in Portland Public Schools, Senate Bill 513 will not change much, rather providing more clarification for what will be taught in each class.

The clarifications give hope for a more equal standard of knowledge and better educated voter population in the future. Each state is able to set its own graduation requirements, this means that the clarifications made by Senate Bill 513 don’t cross state lines.

They also don’t cross age lines. As of now, there is a large population of adults that don’t understand how our government works — an even larger group doesn’t fully understand the Constitution.

So, how fully do individuals understand what they are voting for?

According to a Penn Today survey from 2023, only 66% of American adults could name all three branches of government, and about one in six (17%) were unable to name any. This data is a reflection of both American voters and the American education system. The Penn Today survey also showed that those who had taken a civics class were more likely to respond correctly.

Oregon has started implementing a system that will hopefully bridge the gap between those who are knowledgeable and those who aren’t. But what about the voters who have already finished with their education? Or those who live in a state that doesn’t have that same graduation requirements?

Most of the current seniors and many of the current juniors at Ida B. Wells will be able to vote in the next presidential election. For many seniors who didn’t choose to take AP Government and AP Economy, the last US government class they would have had would have been in 8th grade, with a bit of review in 10th.

There is a difference between a high school level and middle school level of understanding. Having an educated vote means having a more powerful vote; students gain this through a government or civics class.

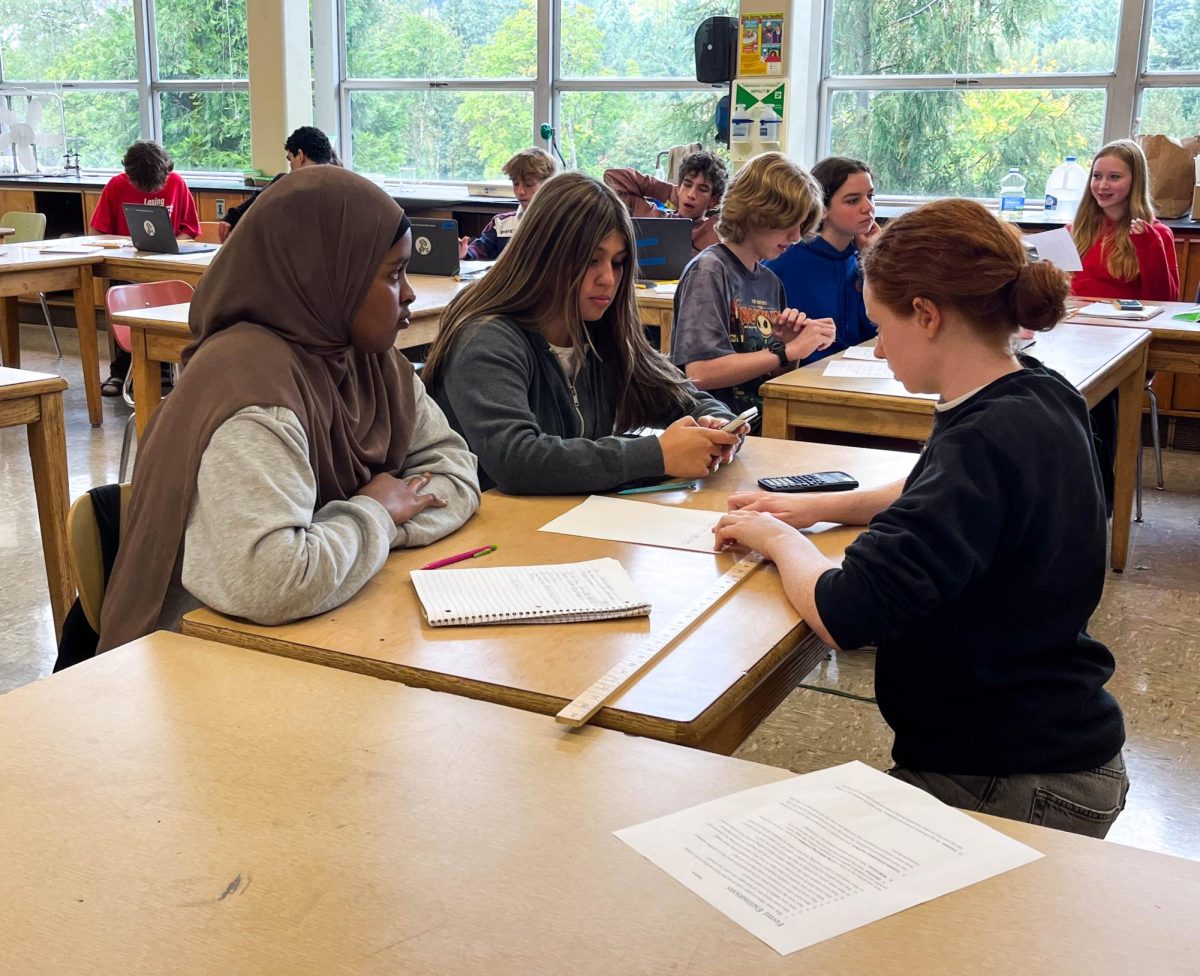

“I want informed voters walking out of my class,” said Tim Loveless, an AP Government teacher here at Ida B. Wells. The class covers five main subjects: branches of government and how they interact, political parties, elections, voting behavior and civil rights and liberties.

“Living in a democracy — we have a pretty huge responsibility to vote and be able to explain our votes,” said Loveless. “And the more kids think about the responsibilities of a citizen, the more kids think about how to make voting decisions — I think the better our government is going to be, because it will more closely represent the people and that’s what a democracy is supposed to do.”

History as a whole is subjective to each individual person’s lived and known experiences so it’s hard to have a set standard for any class that falls underneath that category. Educating students on government structure is not subjective, yet how one chooses to interpret and feel about the constitution and different amendments can be. This can make it more difficult for teachers to fully teach, yet it’s very important for young voters to be able to talk about their perspective, and how to cast a meaningful vote even if they don’t know all the details.

In Loveless’ class, they do just that. “We talk a little bit about what different political parties believe,” said Loveless. “So that as you [students] try and choose between candidates that you maybe don’t know a whole lot about, you can use their party affiliation as a clue as to what policies they might support or not support.” They also talk about another aspect of voting: how to vote when it’s more important to consider who the candidates are than what party they are affiliated with.

Loveless said that he is also willing to share his own views when he teaches, but he doesn’t do it without context or reference to the fact that they aren’t more correct or wrong than another way of viewing it.

“Because I think that the age of new voting at like 18, 19 years old — people who are making voting decisions aren’t necessarily fully in touch with themselves about it,” said Loveless. “And so when kids come to me and they say, ‘Oh, I’m gonna vote for candidate X.’ I start probing that, looking for what about candidate X do you like? You know, are you voting for candidate X, or are you voting against candidate Y? And I try to get the people that I talked to about that to just think more deeply through their decisions.”

I feel lucky that my 8th grade teacher had a similar mindset to Loveless and gave us the opportunity to explore our curiosity and seek a greater understanding, to learn about why and what was actually happening. My teacher telling us to watch the TV wasn’t them trying to get out of that day’s lesson plan but rather having us expand our knowledge in the best way possible — real world application. The next day in class we discussed what we’d learned, what we were confused about and what we were curious about.

I have long awaited the day I can vote — I want my first vote to have value to it, and I will give that significance by understanding what I’m voting for. Thanks to just one or two classes, I will be given a greater understanding of what I’m voting about. If we want to increase the amount of youth who vote, we have to nurture and provide proper support so they feel comfortable casting a vote.