With the start of this winter in tow, there is a lot of talk among Portlanders about the kind of weather we will see this season. Last year, we were met with a cold, wet December, a dry January and a snowstorm in late February. Many are left wondering if we have a similar outcome. However, the big topic that is being speculated is the El Niño winter we are going to experience and its impacts.

El Niño is a climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean that will affect weather worldwide. Under normal conditions in the Pacific, trade winds blow west along the equator, which moves warm water from South America to Asia. Cold water from the depths of the ocean rises to the surface, replacing the warm water, in a process called upwelling. El Niño is one of the climate patterns (the other being La Niña) that breaks these normal conditions.

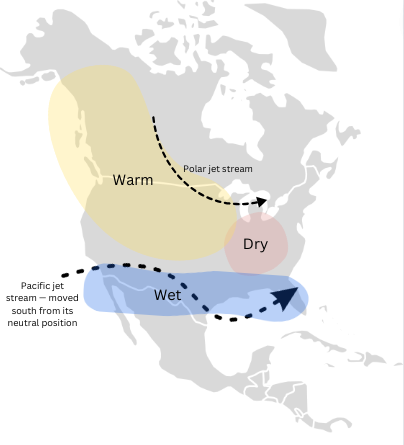

During an El Niño, the trade winds that blow west weaken. This means that the warm water is pushed back east toward the west coast of the Americas. The warmer waters, in turn, cause the Pacific jet stream to move south of its neutral position. The shift in the Pacific jet stream causes areas in the northern US and Canada to experience drier and warmer weather than usual, while the rest of the US and Southeast will experience wetter weather and increased flooding.

In August, the time when projections for winter forecasts are typically announced, there was a ton of speculation about a “super” El Niño occurring this winter. However, according to Rod Hill from KGW8’s Rod Hill’s Winter Outlook, the strength of this winter’s El Niño will only be moderate. To have “super” El Niño the water of the west coast of South America would have to average at least 2℃ and the current temperatures of the water are not even close to that.

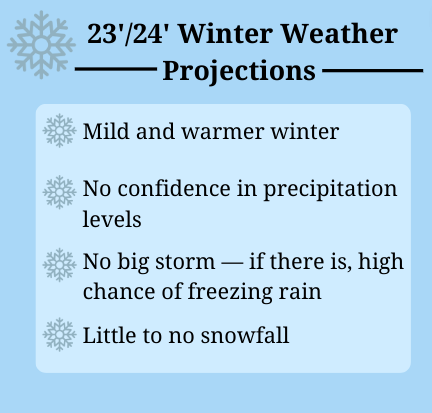

Due to Portland’s close location to the coast, we are in a special situation. Since the Pacific jet stream shifts south, sometimes we miss the precipitation that the Pacific jet stream brings and sometimes we don’t. For example in December 2015, an El Niño winter, Portland had record-high precipitation. According to Rod Hill from Rod Hill’s Winter Outlook, there is no confidence in how rainy this winter will be. Enough El Niño winters in the past have brought high spikes of precipitation to make this uncertain. There is high confidence in projections for a mild, above-normal winter, however. This means that the temperatures will be higher than normal. There will also most likely be no big storm, with little to no snowfall. If there were to be a storm, the chances of freezing rain would be high.

Sadly for skiers, this winter’s El Niño could mean a slow start to the season. AP Biology and Environmental Science teacher at Ida. B Wells, Derek MacDicken, said, “We [ski resorts] are already opening late, so there is a good chance that we are going to have lower initial snowpack, and actually lower snowpack the entire season. Resorts are going to open, no question about that, but it is going to affect a lot of things because it is also the kind of snow that you are going to get. You are not going to get as much of the nice powdery stuff [snow].” Typically in El Niño years, snow is underproduced.

Sydney Collins, a member of the IBW ski team is seeing the effects of El Niño and climate change in general, on her sport. “It’s way warmer up there. When I went up this past weekend it was 50 degrees and there was only 28 inches of snow,” said Collins. “[When it’s drier and warmer] we get less practice, less on-mountain training. It makes it hard, especially for the freshmen, because they don’t get as much training. [This] mainly affects our performance.”

Another impact from El Niño is the negative impacts on marine life. During normal conditions, the upwellings bring the cold, nutrient-rich, water to the surface. During an El Niño, the upwellings weaken. This means that without the nutrients from the depths of the ocean, there will be fewer phytoplankton off the coast, which affects the whole marine ecosystem as phytoplankton are at the bottom of the food chain. The lack of cold water can also displace tropical species into areas that are too cold for them normally.

For Portland, and the entirety of Oregon, this can cause harm to our salmon population, many of which species are already endangered. “When you look at us locally, you don’t get the cold upwelling of water off the coast. That is a huge driving force, not only for currents, weather and all that, but it is a huge driving force for the entire ecosystem off of our coast,” said MacDicken. “When we start seeing more extreme El Niños, that can absolutely decimate our salmon populations, but the thing is, you don’t see that, five years, seven years from that.”

Additionally, the strains of climate change can increase the frequency and amplitude of El Niños. “As temperatures are warmer, the intensity of warm water backing up, because of El Niño, [which can increase] the possibility of having larger oscillations and pushing the jet stream higher, which would give us [Portland] drier conditions consistently in the winter term,” said MacDicken. “We’ll see more extreme swings and we’ll probably see more extreme La Niña swings too.” This means that the side effects of El Niño will amplify too. The dry regions will be drier, which can lead to drought and wildfires. On the other hand, the wet regions will be wetter, and the warm water can encourage hurricanes, other tropical storms and flooding.

Overall, for Portlanders, this winter is projected to be mild with above-average temperatures. For a city in the PNW, the importance of bundling up for rainy, cold weather, may be less prominent this season.

Richard Betts • Jan 3, 2024 at 9:05 am

great reporting on a complicated topic. really enjoyed the quotes from relevant stakeholders!