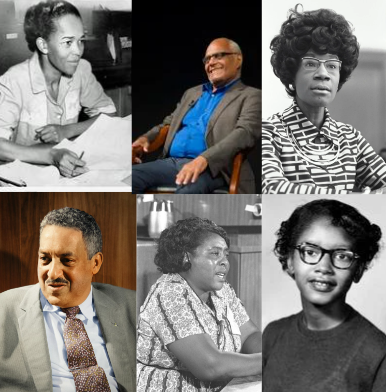

If anyone was asked to name civil rights leaders, most would list Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Rosa Parks. It is also likely that these are the only three leaders they can name. While all these figures are important to know about, it is also vital that other figures are known for their work as well. In honor of Black History Month, here are six civil rights leaders everyone should know about.

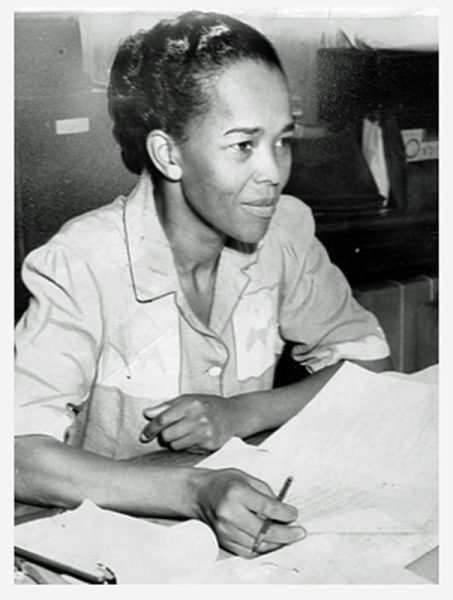

Ella Baker: “Strong people don’t need strong leaders.”

Ella Baker deemed the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” was born in Norfolk, Virginia in 1903. In 1927, she moved to New York City after attending Shaw University. In 1940, Baker joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) but was already working for social improvement since the 1930s. Before joining the NAACP, Baker organized the Young Negroes Cooperative League, a league of groups that pooled community resources together to provide cheaper goods and services to members. She was later recruited by Martin Luther King Jr. to help run the Southern Christian Leader Conference (SCLC), but would go on to leave the conference to form a group called the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) along with other young leaders. SNCC organized sit-ins, freedom rides and other nonviolent protests throughout the South. During her time with SNCC and the other groups she previously worked with, Baker helped young people find their voice and encouraged them to fight racism, white supremacy and sexism. She single-handedly raised a generation of civil rights leaders. However, not wanting publicity or financial acclaim, Baker decided to stay behind the scenes, a major reason for the unawareness of her and her work today.

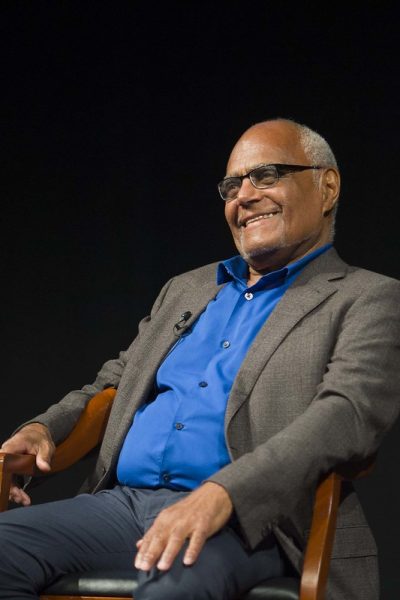

Bob Moses: “Leadership is there in the people.”

Bob Moses was born in 1935 in New York City. He graduated from Harvard University with a master’s in philosophy in 1957 but would go on to be a math teacher at Horace Mann School. At the same time, Moses started his involvement in the civil rights movement and ended up becoming one of its most influential leaders. Woken up and inspired by sit-ins occurring in the South, Moses initially began his work in 1959 by helping Bayard Rustin, a political activist and leader of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, with the second Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington D.C. This work soon led him to Atlanta, Georgia, where he first worked with SCLC and later traveled on behalf of SNCC on a recruiting tour. While on this tour he met Amzie Moore, a NAACP activist, whom Ella Baker connected him with. Moses’ connections with Moore began SNCC’s efforts to expand voter registration in the South. In 1961, he became a part of the SNCC’s staff as the special field secretary for voter registration in McComb, Mississippi after being a volunteer. A year later, he also became the co-director of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), a collective organization of civil rights groups in Mississippi. He resigned from his role at COFO in 1964 due to concerns about his role becoming too centralized. Moses’s influence went far and wide as he nurtured and recognized local leaders and guided them to be effective organizers. In particular, Moses developed the ideas for the Freedom Summer Project and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), two projects that Fannie Lou Hamer would later take on. His experience with organizing would help Moses later in his life too. In 1982, Moses started the Algebra Project, a national program that aimed to improve the math skills of children in underprivileged communities.

Shirley Chisholm: “Unbought and unbossed.”

Shirley Chisholm was born in 1924 in Brooklyn, New York. A graduate of Brooklyn College and the Teachers College at Columbia University, she was originally a teacher but became a politician. In 1968, Chisholm became the first African-American woman to serve in the U.S. Congress. She began her seven-term service as a congresswoman in 1969 and challenged systemic racism and sexism, as well as significantly impacting anti-poverty and education reform policies throughout her political career. However, Chisholm did not stop at Congress. In 1972, Chisholm was the first African-American woman to be a presidential candidate. Subsequently, she became the first Black person who sought a major party’s nomination for president, as well as the first woman to run for the Democratic party’s presidential nomination. She coined the slogan, “Unbought and unbossed,” for her campaign. Although she lost the nomination, Chisholm would still go on to serve 11 years in Congress, but more importantly, she was a national symbol of the intersection of civil rights and women’s rights.

Thoroughgood ‘Thurgood’ Marshall: “Where you see wrong or inequality or injustice, speak out, because this is your country. This is your democracy. Make it. Protect it. Pass it on.”

In 1908, Thurgood Marshall was born in Baltimore, Maryland. He graduated from Howard University after being initially rejected from the University of Maryland Law School because he was not white. He was encouraged by Charles Hamilton Houston while at Howard University to view the law as an outlet for social change; Marshall did just that. In 1936, he became a staff lawyer under Houston for the NAACP. Two years later, Marshall was the lead chair in the legal office of the NAACP and another two years later he was granted the position of chief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. During his years as a lawyer, he built up a reputation as an advocate for social justice and established his place as one of the top lawyers in the U.S. by winning 29 out of 32 cases he argued in the Supreme Court. His most famous case was Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), where he represented the Brown family and led them to a unanimous decision that overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). This was a major feat as it made segregation unconstitutional. In 1967, Marshall became a Supreme Court justice and used his platform to continue to advocate for African-American rights and equitable treatment of minorities. Even with the added challenge of a conservative majority in the Supreme Court during his later years of service as a justice, Marshall was an unwavering figure of social justice in the court.

Fannie Lou Hamer: “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

Born in Montgomery County, Mississippi in 1917, Fannie Lou Hamer experienced racism at a young age. Limited to a sixth-grade education in the need to help her sharecropping parents on the fields as well as receiving a non-consensual hysterectomy from a white doctor, her experiences with injustice primed her to become one of the most powerful voices in civil rights, voting rights and economic opportunities for African Americans. Hamer became a SNCC organizer in 1962 and led an effort of 17 volunteers to register to vote in Indianola, Mississippi. She was denied registration by an unfair literacy test, was then fined $100 by police for the volunteer bus being “too yellow,” and was later fired from the plantation she worked on due to her attempt to register to vote. Nonetheless, Hamer persisted. In 1963, she successfully registered to vote in Charleston, South Carolina.

In 1964, Hamer co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which aimed to challenge the barring of Black participation in the local Democratic Party. She and other members of MFDP went to the Democratic National Convention arguing to be recognized as the official delegation instead of the Mississippi Democratic Party. They also testified before the Credentials Committee of the Democratic National Convention for a mandatory order of integrated state delegations. President Lyndon B. Johnson attempted to stop Hamer’s testimony from getting televised airtime by scheduling a press conference at the same time. Johnson’s efforts failed with Hamer’s speech being televised at a later time, causing her story to get more exposure, as well as, spreading her message of racial prejudice and injustice that civil rights leaders experienced. That same year Hamer organized Freedom Summer, an effort by hundreds of black and white college students to help African-American voter registration. Hamer also became a candidate for the Mississippi House of Representatives but was not listed on the ballot. In 1965, she protested the recent Mississippi House election in the U.S. Congress with other Black women, due to her being barred from the ballot. Hamer would go on to found the National Women’s Political Caucus a couple of years later.

Taking a new angle, Hamer took action to create economic opportunities for Black people to progress to equality. She began a “pig bank” in 1968 to provide free pigs for Black farmers and created the Freedom Farm Cooperative (FFC) in 1969, where she bought land that would be owned and farmed collectively by African Americans. Until the mid-1970s, the FFC was one of the largest employers in Sunflower County, Mississippi.

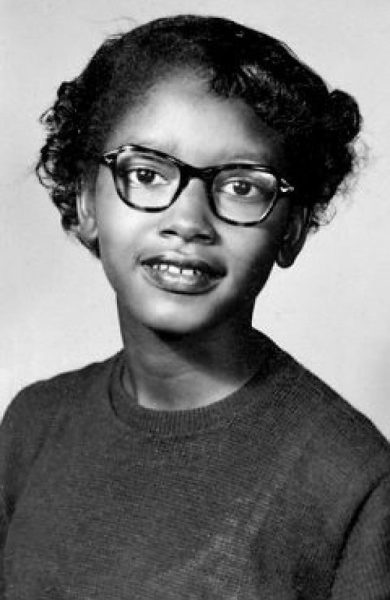

Claudette Colvin: “History had me glued to the seat.”

Claudette Colvin, the “Rosa Parks before Rosa Parks,” was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1939 and grew up in Montgomery. At just 15, Colvin was arrested for refusing to give up her seat in a segregated bus and not moving to the back. This occurred nine months before Rosa Parks’ arrest in the same bus system and city. Colvin was considered to be the face of the movement to end bus segregation, but she was deemed too young and had too dark of a complexion to be the right fit. She also became pregnant, another reason why leaders considered her to be unfit for the role. Colvin continued her fight by taking her case to court as one of the key female plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle which successfully overturned bus segregation laws in Montgomery, Alabama. Later, Colvin moved to New York City, where her story was overshadowed by Malcolm X’s popularity and his philosophy of Black power.

While you now know about six more civil rights leaders, they are just a few among the many trailblazers for racial equality and equity in America. “There’s amazing people that do amazing things all over the place. Some of them get national spotlight and fame, some of them don’t,” said social studies teacher Max Trezise at Ida B. Wells. “It’s really special to try and give credit to, or at least celebrate, these people that you otherwise might not have ever heard of.”