With fall in full swing and Halloween quickly approaching, horror movies are back to set the spooky mood. However many are often too distracted by the Halloween spirit to notice the harmful portrayal of women in their favorite horror movies. The horror genre, typically the slasher subgenre, has long been used as a way to punish women for their sexuality.

The main goal of horror is, naturally, to scare. Due to this, viewers are less likely to dissect the movie’s substance and instead focus on how they felt throughout. This approach easily overlooks the subtle sexism woven into the subtext.

The “final girl” trope is nearly innate to slasher films. It’s seen in almost all classic slashers such as Halloween, Black Christmas, Friday the 13th, Scream, the Texas Chainsaw Massacre and many more. The term “the final girl” was first coined in 1992 by author and professor Carol J. Clover, in her book “Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film.” The final girl is the female character, often deemed iconic by the audience, who manages to survive the killer until the end of the film and win the fight with the murderer, whatever form that may take.

At first, this seems to be a trope worth celebrating; out of everyone, the one who survives and saves the day is a girl, defying stereotypes because she is not a helpless victim. However, upon further inspection, this pattern is not as progressive as it may seem.

Right off the bat, it’s clear who this “final girl” will be, she is set apart from others by her lack of promiscuity, partying and femininity. It is for these traits that the “final girl” survives and avoids the brutal deaths her female counterparts suffer. The latter is typically the opposite of the final girl, she flaunts her body and sexuality unabashedly. Then, when her death inevitably arrives, it is less a tragedy and more a rightful punishment.

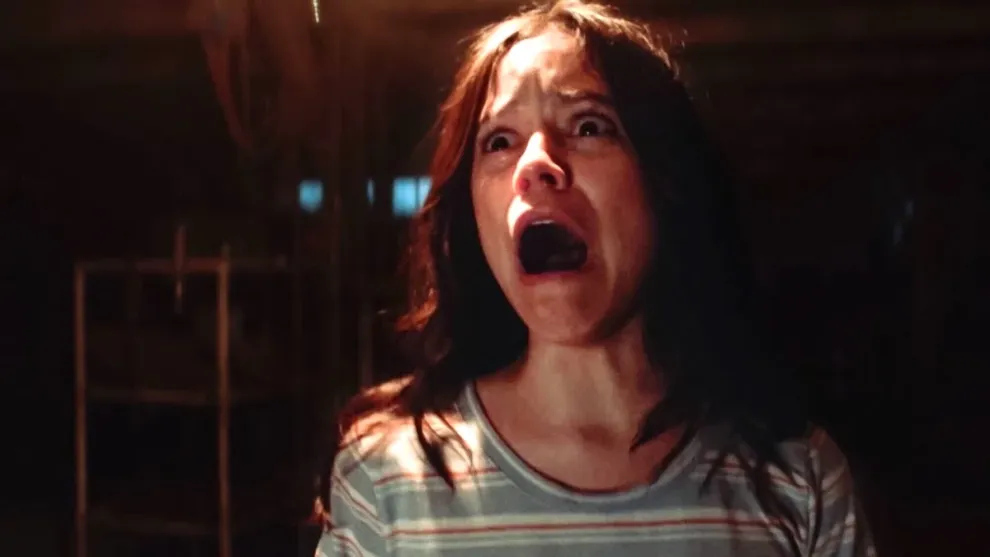

Clover describes the slasher movie as, “encroaching vigorously on the pornographic,” likely due to the way female murders or assaults are often shown, adjacent to what some would call a male fantasy. A prime example is the Evil Dead franchise, where female deaths are taken to another level. In the 2013 remake of the original, there are scenes of girls murdered in the shower, running from the murderer nude and stuck in traps in only their underwear; the list still goes on. This display of violence is far from uncommon in the genre, which raises the question of whether these unnecessary and exaggerated murder scenes are intended to scare or to please.

In recent years, there’s been pushback. This is best seen in Ti West’s X trilogy, consisting of the movies X, Pearl and the recently released Maxxine, all starring actress Mia Goth. In X, the protagonist Maxine, is an ambitious sex worker and the sole survivor of the movie, actively defying the “final girl” description and remains a fleshed out character while having a firm grip on her sexuality.

But where do we draw the line between empowerment and over-sexualization? While X does a great job at opposing the “final girl” trope, some may argue that it still feeds into the male gaze because of Maxine’s confident display of sexuality, even though the two do not necessarily equate to each other.

Whether a trope is deemed problematic or not, the idea that women in media must fall into a given archetype is questionable. Focusing on opposing stereotypes in media, it is easy to form another like the “final girl.” Creating a female character who is truly a character, rather than a trope, is the first step to reforming the horror genre as something terrifying in a way other than everyday sexism.