“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” states the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

We’ve seen party affiliation with religious sects since the dawn of America, originally founded on Anglican ideals. As the progression of social justice and a rising call for bipartisan politics has unfolded over the last 150 years, it seems that the logical passage through contemporary thought draws a distinct line between religion and government. However, the recent election raises questions of whether or not faith systems really have sway in political matters.

God Bless America

We’re all familiar with the wistful story of how America came to be: Puritans fleeing the oppressive Church of England sought a new world free of religious persecution, and more importantly, Catholics. Those first settlers eventually established the thirteen colonies, after an extensive period of significantly denting the Indigenous populations and clearing way for an influx of European immigrants. From those first seekers of religious asylum, the great nation of the United States of America was born, with its plethora of convoluted documentation.

The motivating ideals of the Constitution have been questioned since they were first transcribed into law in 1787. That’s why the U.S. Supreme Court was organized – to interpret the Constitution and debate governmental actions and policies’ adherence to it.

There is definitely a distinct trend in human civilizations following historical patterns to govern individual lives and dictate morality. But the two that hold the most power over the U.S., the Constitution and Christian scripture, come from very different eras and viewpoints, and promote very different rules of governance. Sure, there’s crossover, and one can easily identify the influence the Bible has over the Constitution and its sister documents (we are a “nation under God” after all), but the context of the two makes all the difference.

Where does religion belong in a modern nation like ours? Is it even possible for governments to operate isolated from faith systems? And most importantly: what does this have to do with Donald J. Trump’s recent electoral victory?

Contemporary Trends

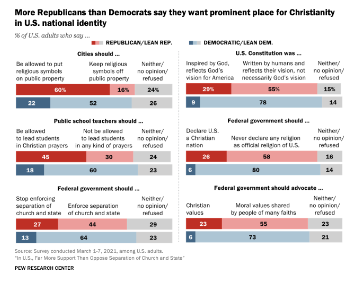

Research done by the Pew Institute in 2021 illustrates the trends in advocating for religious governance. “For instance, three-in-ten say public school teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers, a practice that the Supreme Court has ruled unconstitutional. Roughly one-in-five say that the federal government should stop enforcing the separation of church and state (19%) and that the U.S. Constitution was inspired by God (18%). And 15% go as far as to say the federal government should declare the U.S. a Christian nation.”

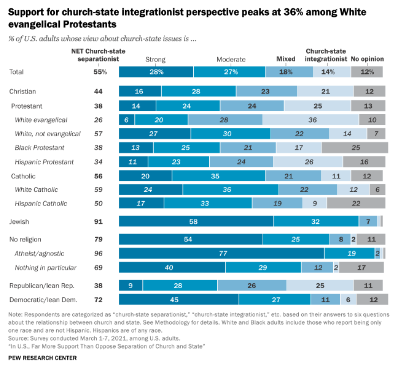

The percentage of church-state integration advocates might seem insignificant as a minority, but there is still one-in-five Americans who hold beliefs supporting a Christian nation. The Pew Institute’s survey also determined that White Evangelical Christians are most likely to advocate for religion in public policy compared to other Christian sects and religious orders.

Trump and Harris

Where America stands out from other countries home to significant populations of Christians is the evocation of faith systems in political rhetoric. While almost every single U.S. president has been a part of the Church, specifically the Protestant branch, the words of ex-candidate Donald Trump have trailblazed the way by explicitly showing favor to his “beautiful Christians.”

Trump’s promises to “save religion in this country” encroach on that familiar politician ambiguity, but leave little room for interpretation. Trump believes this is a country for Christians, and Kamala Harris is the number one enemy of the utopia Trump hopes for. Throughout his campaign, Trump supporters consistently framed his liberal opponent as “anti-Christian” and “anti-Catholic,” highlighting her multifaith views for America as a threat to the church.

What didn’t aid in the downfall of the Harris campaign was the stark contrast between Harris’ ethnically diverse and secular America versus Trump’s Christian vocational America. Neither candidate had much appeal to the other’s supporters in that sense. It was one or the other.

And people aren’t afraid to take action when pursuing their political ideals, as is painfully obvious every year. The Guardian’s interview with protesters at a conservative rally at the National Mall on October 12 demonstrates the passion held in the hearts and minds of some subscribers to right-wing ideals.

“‘I was here [on] January 6,’ said Tami Barthen, an attendee from Pennsylvania to attend the rally, and who described her experience of the Capitol riot as profoundly spiritual. ‘It’s not Democrat versus Republican… It’s good versus evil.’”

The “good versus evil” mentality permeating politics almost guarantees protests and violence. There are people who are so terrified of a Democrat or Republican-controlled legislature, that they’re willing to resort to whatever it takes to avoid it.

The “good versus evil” mentality permeating politics almost guarantees protests and violence. There are people who are so terrified of a Democrat or Republican-controlled legislature, that they’re willing to resort to whatever it takes to avoid it.

Pew Institute conducted a survey in 2021 finding that “White adults with church-state integrationist views are much more likely than White church-state separationists to say Trump was a good or great president (by a margin of 59 percentage points), to identify with or lean toward the Republican Party (by 54 points), to say that immigrants threaten traditional American customs and values (47 points), and to say that society is better when people prioritize getting married and having children (42 points). They also are 35 points more likely to say that being Black is no more difficult than being White in the U.S. today, and 32 points more likely to say the U.S. has a unique place above all other countries in the world.”

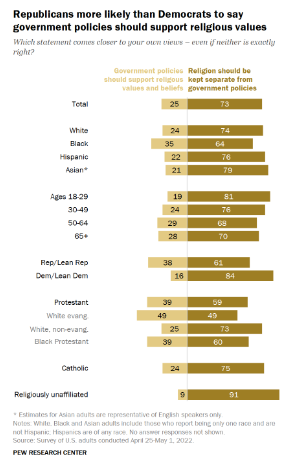

Let’s break that down. White individuals with hopes for religious rhetoric in schools and governments are more likely to support the Republican Party, Trump, anti-immigration oratory, and traditional family values. This is nothing new, but it does lend credence to the claims that the Republican Party is more and more consistently catering to Christian ideals.

“I think that there is a religious component to it,” says Tim Loveless, the AP U.S. Government and Comparative Government teacher at Ida B. Wells. “I think that the outlawing of abortion motivated a lot of very conservative religious people to vote for Donald Trump, and I think that [he] made a specifically religious argument as part of his campaign in a way that Harris did not. I consider myself a Christian, but there are certain pieces of Christianity that I disagree with pretty significantly. And I would not want somebody else’s beliefs forced upon me.”

“I think that there is a religious component to it,” says Tim Loveless, the AP U.S. Government and Comparative Government teacher at Ida B. Wells. “I think that the outlawing of abortion motivated a lot of very conservative religious people to vote for Donald Trump, and I think that [he] made a specifically religious argument as part of his campaign in a way that Harris did not. I consider myself a Christian, but there are certain pieces of Christianity that I disagree with pretty significantly. And I would not want somebody else’s beliefs forced upon me.”

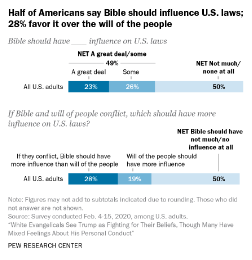

According to Pew, half of Americans favor Biblical teachings in the U.S. legislature.

What the Future Holds

“I think that we will see more racism in our country. More attacks on disadvantaged populations. More xenophobia,” says Loveless. “I think we’re going to experience some economic pain over the next couple of years, probably mostly in higher prices, but also potentially in higher unemployment. I think that the wars in Ukraine and in Palestine are going to end in pretty spectacular fashions. I think that women’s rights will be rolled back.”

It was the last item on his list that struck a chord. It’s impossible to describe the feeling I experienced at that moment, sitting in the library, hearing a history teacher say with great solemnity, “Women’s rights will be rolled back.” Loveless has two teenage daughters my age.

What kind of world are we living in?

That question will undoubtedly be asked repeatedly over the next four years, in hushed tones as people watch the news, in indignant shouts at protests and rallies and in tearful confessions slumped on bathroom floors.

As these questions surround our anxious minds, the end result may lie in whether we as individuals choose to uphold inclusivity or further solidify the painful divide our anxieties stem from.