Affinity months are a fairly recent development, but a well-publicized one. Beginning in 1976, we’ve worked our way up to both official and unofficial celebrations for eleven out of twelve months, the one exception being January, which does not have a delegation to date.

Below are the officially and unofficially recognized affinity months:

There are a few discrepancies between the affinity months commonly celebrated by different communities and the affinity months recognized by the federal government. Notably, and one that will unfortunately likely continue to be omitted in the next four years, is Pride Month. The federal government has a long and tumultuous history of contention with the LGBTQ+ community, and the absence of Pride Month is hardly surprising, but it is one of the most commonly recognized affinity months by most Americans, rather it be in a positive or negative sense.

June was recognized as Gay and Lesbian Pride Month in 1999 by former president Bill Clinton, thirty years after the Stonewall Uprising, widely considered the beginning of the Gay Rights Movement, a catalyst in the LGBTQ+ community. However, today it is not federally recognized.

The U.S. State Department omits LGBTQ+ Pride Month, South Asian Heritage Month and Deaf History Month, both months dedicated to disability awareness and celebration, Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention month, LGBTQ+ History Month and Native American History Month from its roster. In fact, the U.S. Government only recognizes nine designated appreciation or celebration months.

Not all affinity months are universal or part of mainstream media. Black History Month and Pride Month are both often at the forefront of the discussion, but some like Native American History Month and Disability Employment Awareness Month aren’t as recognized as some believe they should be.

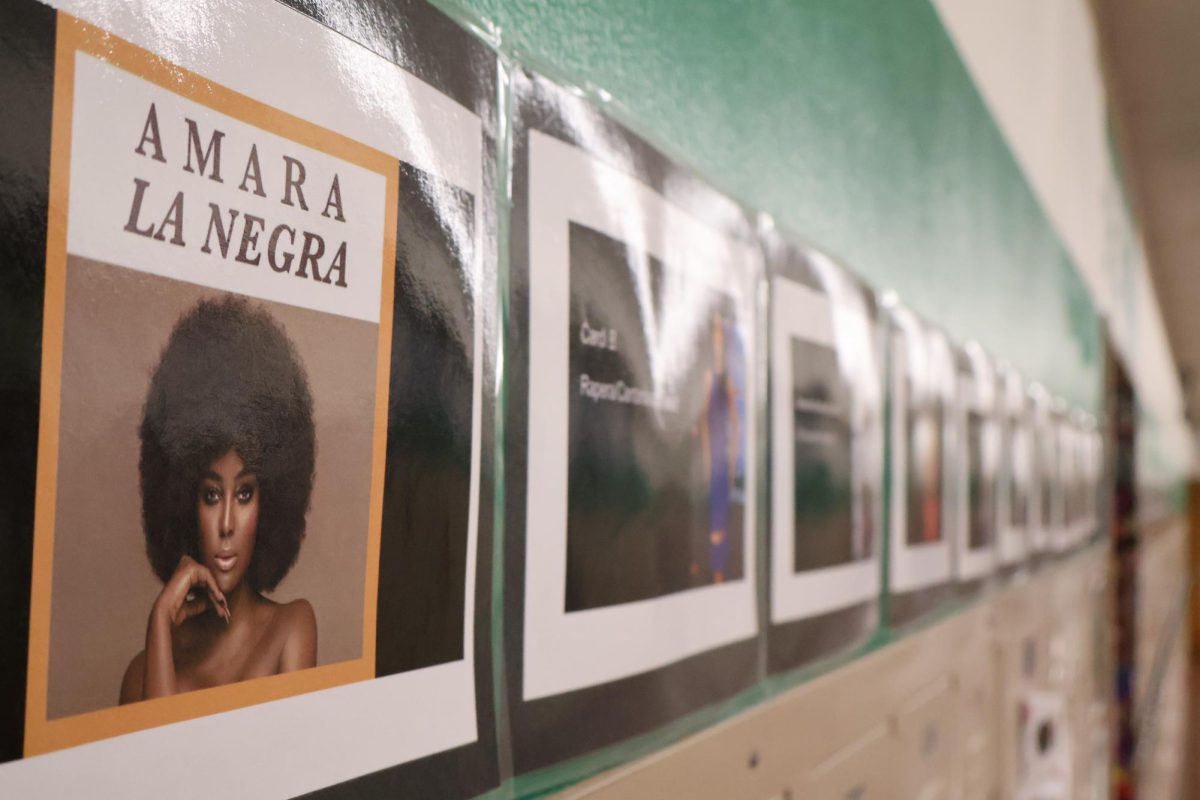

Affinity months have proven to be important to the communities they celebrate, creating spaces for appreciation and critical thinking about and within minorities in America. “I think it’s important for high school students specifically who represent, who affiliate themselves with those particular groups of people that are celebrated each month, to have an opportunity to really elevate their voice, elevate their experience and to feel a sense of pride in their history and in their cultural identity,” says Ida B. Wells-Barnett Principal Ayesha Coning. “And so, even though we want our students and our young people of all different backgrounds to feel welcomed and included and elevated the entire school year, we know that in a community where our students of color are the minority [about 20% of our student body are students of color] that we want to go the extra mile to make sure they feel seen and heard.”

“It feels really good to know that we are getting to influence and share our history with others even though there was a positive and negative history with our people. It makes me feel that I’m a part of history and my ancestors are part of history. And me being from West Africa, Sierra Leone, getting to just share the culture makes me feel really good, that I’m still alive to be able to come forth and speak on what’s right for people,” IBW senior and Black Student Union Co-President Sebastien Porter says. “I’m very grateful and thankful that we’re getting support, and I do feel supported by the faculty and my peers, and I feel heard.”

Black History Month began as just a week in 1926, instated by American scholar, author and activist Dr. Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950). Woodson was one of the first official academics to study African-American history and founded the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

In 1976, the Ford Administration prolonged the original week to the entire month of February, chosen because it harbors the birthdays of both Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Douglass (1817-1895) was an activist, writer, lecturer and editor, who escaped slavery at 21 and campaigned for its abolition by delivering speeches and establishing a newspaper in 1847, “The North Star.” Lincoln, our sixteenth president, issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, federally abolishing slavery in the United States (although the ending of the system, nationally, isn’t recognized until Juneteenth, June 19).

One of the reasons for pushback against affinity months historically has been the exclusion of communities not represented in designated months. At the forefront is the admonition, “well, what about a White History Month?”

This is a question that seems innocuous enough, but comes from a place rooted in unintentional (or intentional) aggression.

“[Asking about] ‘White History Month’ in response to Black History Month minimizes the struggles and accomplishments Black individuals have had in order to even get a month to themselves. We are celebrating Black excellence, and the contributions they have made to America,” Porter says. “I feel like it shouldn’t have to be that we need our own month, but we need our own month.”

“When I was in high school in the 80s, the history that we were taught was steeped in the white male experience. We did not learn African-American history from the perspective of African Americans. We did not learn Native American history from the perspective of Native Americans. We learned about the history from a white male colonizing perspective, which historically is about conquest and colonization. So our country’s foundation and the history that’s been told for hundreds of years, 250 years, is based upon the white European colonizers’ experience. So it is opening up a door for all the generations that have come before this younger generation, before your generation, [who] only learned that narrative of the European colonizer,” says Coning. “And so now, I would say, as an elder, older person, we’re grounded, we’re rooted in a history that is centered on white voices. And that’s why there’s not a ‘White History Month.’”

“And I would say all the histories are important, it’s all super important and really looking at how they intersect and also how they vary, how they’re different is really important.” Coning continues. “The history of African Americans from an African American perspective is a very different story than the history of African Americans told by white colonizers.”

In the end, affinity months are about perspective, and adding points of view to a larger conversation when they might be drowned out or ignored. During those times, it’s important to remember that lifting up voices doesn’t mean pushing down others.

For non-affinity members during months like February, Principal Coning has advice on how to lift up these celebrations: “Be good listeners. Ask questions, be empathetic and help forge positive relationships with each other.”

Don’t be afraid to ask questions this February, and in the months to come, because learning about each other and our individual and shared histories is the best building block for a brighter future.